by M | Jul 24, 2020 | News |

The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) has helped home-based care providers/Home Care Agency who received less than $150,000 in loans save more than 160,000 jobs nationwide, according to data from the Small Business Administration (SBA).

States such as Texas, California and Florida saw the highest number of home-based care jobs retained as a result of the program. Meanwhile, unlikely suspects such as Idaho, Ohio and Missouri saw PPP-recipient agencies retain the most home-based care employees on average.

Home Health Care News discovered those trends while analyzing July 14 PPP data from the SBA. That data includes the number of workers employed by each PPP recipient, as well as the total loan amount granted to each awardee.

For the analysis, HHCN sorted the federal SBA data by NAICS code to identify home-based care PPP recipients that received less than $150,000. From there, HHCN broke the data down on a state-by-state basis.

The North American Industry Classification System, or NAICS, is a classification of business establishments by type of economic activity. NAICS codes are used by government agencies and businesses in Canada, Mexico and the U.S.

Home-based care providers in HHCN’s analysis include all those with the NAICS code 621610, which is used for “establishments primarily engaged in providing skilled nursing services in the home.” In addition to home care and home health agency, that includes businesses in realms such as home infusion therapy and in-home hospice, among others.

In total, PPP loans helped more than 15,000 home-based care agencies retain a combined 160,175 jobs, the data suggests. In other words, that’s how many aggregate workers are employed by those loan recipients, who might otherwise have gone out of business without the PPP money.

HHCN has yet to review the data for providers that received more than $150,000 in PPP loans.

Contextualizing the numbers

PPP was created by the CARES Act to help small businesses navigate the COVID-19 emergency. It set aside billions of dollars in forgivable loans for businesses across a bevy of industries, including home health and home care.

One of the biggest goals of the program is to help businesses keep their workers employed. As such, an important condition of loan forgiveness is that recipients must keep up their staffing levels and wages.

If a PPP loan recipient doesn’t have a full-time employee count equivalent to pre-coronavirus levels by Dec. 31, that recipient won’t be eligible for full loan forgiveness. It will have to pay back a portion of the costs.

Consequently, the aforementioned SBA PPP job retention numbers assume that all PPP recipients will keep the employment levels they had when they applied for their loans. That data could be incomplete.

“PPP loan data reflects the information borrowers provided to their lenders in applying for PPP loans,” an SBA spokesperson told HHCN in an email. “SBA can make no representations about the accuracy or completeness of any information that borrowers provided to their lenders. Not all borrowers provided all information.”

Additionally, it’s worth noting that some PPP home-based care recipients could fail to meet the requirements of the program and lay off employees anyway.

State stars

Texas saw the most home-based care workers retained as a result of PPP loans, with 21,541 employees at recipient agencies benefiting.

California and Florida retained the second and third highest number of home-based care jobs. In California, that number was 19,186, while 11,039 jobs were saved in Florida.

Those numbers make sense in context of the large amount of PPP funding Texas, California and Florida received. In a previous analysis, HHCN found that those three states saw the most agencies receive loans, with more than 5,400 home-based care recipients getting about $224 million combined.

Meanwhile, the trends in Idaho, Ohio and Missouri were more surprising.

For example, Idaho of all states saw its 60 home-based care PPP recipients who got less than $150,000 retain the most employees on average, at about 20 each.

Meanwhile, Florida agencies, by comparison, retained an average of only six jobs each.

While it’s unclear exactly why Idaho home-based care PPP recipients retained the highest number of workers, Robert Vande Merwe, executive director of the Idaho Health Care Association, speculated it could be a result of low wages.

“Idaho still has the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour,” Vande Merwe told HHCN in an email. “And the Medicaid rate is VERY low for home care.”

Joe Russell, executive director of the Ohio Council for Home Care & Hospice, had other ideas for his state, in which agencies retained an average of 17 jobs each with PPP funding.

He said the average pay rate for an aide in Ohio is about $13 per hour.

“I would venture to guess that those states that have a higher number of jobs saved are probably looking at a larger number of larger agencies getting these PPP loans,” Russell told HHCN.

That appears to be true in the case of Idaho, Ohio and Missouri, the lattermost of which also saw agencies retain an average of 17 jobs each.

But agencies big and small and in those states and beyond continue to need state and federal financial support in addition to PPP, according to the Missouri Alliance for Home Care.

“While the PPP monies did greatly benefit some in the home care industry, the enormous cost of additional personal protective equipment (PPE), decreased utilization, additional staffing, overtime, hazard pay, etc., has had enormous revenue impacts on home care providers,” Carol Hudspeth, executive director of the Missouri Alliance for Home Care, told HHCN in an email. “As a result, the home care infrastructure is in great jeopardy at a time when it is needed the most.”

By Bailey Bryant | July 22, 2020

Source: Home Health Care News

by M | Jul 23, 2020 | News |

Everyone involved even tangentially in Home Care Agency today is consumed by the coronavirus pandemic, as they should be. But the pandemic is accelerating a problem that used to be front and center in health circles: the impending insolvency of Medicare.

With record numbers of Americans out of work, fewer payroll taxes are rolling in to fund Medicare spending, the number of beneficiaries is rising, and Congress dipped into Medicare’s reserves to help fund the COVID-19 relief efforts this spring.

“I think we have a real, impending health care crisis,” said Dr. David Shulkin, who was undersecretary for health at the Department of Veterans Affairs under President Barack Obama for two years and led the VA for a year under Donald Trump.

In April, Medicare’s trustees reported that the Part A trust fund, which pays for hospitals, Home Care Agency, and other inpatient care, would start to run out of money in 2026. That is the same as the projection in 2019. But the trustees cautioned at the time that their projections did not include the impact of COVID-19 on the trust fund.

“Given the uncertainty associated with these impacts, the Trustees believe that it is not possible to adjust the estimates accurately at this time,” said the report.

So Shulkin, now a senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, did his own projections in early July. Given even a conservative estimate of how many workers and businesses would not be contributing payroll taxes that finance Part A spending, he said, the trust fund could become insolvent as early as 2022 or 2023.

“I think this is something that needs more immediate attention,” he said.

Others who make projections agree the insolvency date is getting closer, maybe not as close as 2022.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonpartisan group of budget experts focused on fiscal policy, estimates that the pandemic will cause the Part A trust fund to be unable to pay all of its bills starting in late 2023 or early 2024. “But we’re still very close,” said Marc Goldwein, the group’s senior vice president.

There are two ways the trust fund can get into trouble: Either the money flowing in is too little, or the payments going out for care are too much.

Most of those who watch Medicare finances agree that the larger problem right now is how much money is being collected for the trust fund. That money largely comes from the 1.45% payroll tax paid by employees and employers. With so many people out of work because of pandemic-related shutdowns, cash flowing in has dropped dramatically.

It’s far less clear what is happening on the spending side of Medicare Part A. (Medicare Part B, which pays physicians and other outpatient costs, is funded by beneficiary premiums and general tax funding, so it cannot technically become insolvent.)

While coronavirus-related hospital expenses for those on Medicare are expected to be substantial, Medicare hasn’t been reimbursing as much care of other sorts. In some cases, that’s because hospitals in COVID hot spots temporarily stopped doing elective procedures like joint replacements. In other cases, patients with non-COVID-19 ailments have been afraid to go to hospitals for fear of catching the virus.

Also, said Goldwein, Home Care Agency/health care use tends to fall in recessions, even for Medicare, whose beneficiaries are largely retired.

In the end, he said, “we basically threw our hands up and said we don’t have the information” to estimate how health costs will affect the trust fund’s financing.

There is one other coronavirus-related policy that could hasten the depletion of the trust fund. At least $60 billion of the funding provided as part of the CARES Act to help hospitals weather the pandemic came not from the general treasury, but from the Trust Fund itself.

That money in “accelerated and advance payments” is supposed to be paid back, via a reduction in future payments. But there is a push in some quarters for that funding to be forgiven, which would make the trust fund’s hole even bigger.

It is not exactly clear what would happen if the trust fund were to become insolvent because it has never happened before. It is important to remember that the fund becoming “insolvent” is not the same as being “bankrupt.” Insolvent means the Trust Fund would still have money flowing in, but not enough to pay for all the care Medicare patients will consume.

Most budget experts think that Medicare would reimburse hospitals and other Part A providers 100% of their claims until the fund literally runs out of money, and then would pay claims only as more money flows in.

Others think Medicare might reimburse only a percentage of those claims, but that might require congressional action.

Meanwhile, one would expect the hospital industry to be ringing the alarm bells as potential insolvency approaches. But that’s not happening.

“They’re more concerned with next month than with 2023 at this point,” said Goldwein.

Chip Kahn, president and CEO of the Federation of American Hospitals, agreed. “I’m not going to worry about this right this minute,” he said. “At this point, my focus is completely on COVID.”

By Julie Rovner | July 21, 2020

Source: NPR

by M | Jul 21, 2020 | Blog, News |

During the Coronavirus pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has taken unprecedented action to expand telehealth for Medicare beneficiaries. Since people were advised to stay at home to reduce risk of exposure of COVID-19, there was an urgency to increase access to telehealth services to help people who need routine care and allow beneficiaries to remain in their homes. Early CMS data have shown telehealth to be an effective way for people to access Home Health Care Service safely during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether it’s getting a prescription refilled, managing chronic conditions, or obtaining mental health counseling.

Today, we share data highlighting the impact of telehealth on beneficiary access. We also discuss how we are using this information to assess whether these expanded telehealth policies should remain in place beyond the COVID-19 public health emergency.

Telemedicine—which includes telehealth and other virtual services—allows patients to visit with clinicians remotely using virtual technology. Innovative uses of this kind of technology in the provision of Home Health Care Service are increasing with advances in telehealth platforms and remote patient monitoring technology. New mobile health apps and wearable monitoring devices help track a patient’s vitals, provide alerts about needed care, and help patients access their physician. CMS has long prioritized telemedicine innovation, but COVID-19’s emergence in the U.S. prompted us to drastically accelerate our efforts.

On March 13, 2020, President Trump made an emergency declaration under the Stafford Act and the National Emergencies Act, empowering CMS to issue waivers to Medicare program requirements to support Home Health Care Service providers and patients during the pandemic. One of the first actions CMS took under that authority was to expand Medicare telehealth on March 17, 2020, allowing all beneficiaries to receive telehealth in any location, including their homes. Subsequently, CMS announced additional temporary rules and waivers to expand the scope of Medicare telehealth services, making it easier for more types of health care providers to offer a wider range of telehealth services to beneficiaries across the country. CMS observed immediate, dramatic increases in telehealth services.

With these transformative changes unleashed over the last several months, it’s hard to imagine merely reverting to the way things were before. As the country re-opens, CMS is reviewing the flexibilities the administration has introduced and their early impact on Medicare beneficiaries to inform whether these changes should be made a permanent part of the Medicare program.

CMS Actions To Expand Telemedicine Before COVID-19

By law, Medicare can only pay for most telehealth services in limited circumstances: when the person receiving the service is in a designated rural area and when they leave their home and go to a clinic, hospital, or certain other types of medical facilities for the telehealth service. A telehealth service must use an interactive audio and video telecommunications system that permits real-time communication between the distant site practitioner who is remotely furnishing the service—such as a physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant—and the patient at a local medical facility.

The Trump Administration recognized the value of telemedicine for patients and home health care providers long before the pandemic, as part of CMS’s Fostering Innovation Strategic Initiative, the agency’s comprehensive strategy to improve patients’ access to emerging technologies. That’s why over the last three years CMS made several changes to improve access to virtual care. We expanded the services that can be delivered via telehealth, adding services such as wellness visits that require additional time for complex patients and care for patients experiencing a stroke or with End Stage Renal Disease.

In 2019, Medicare started paying for brief communications or Virtual Check-Ins, which are different from traditional Medicare telehealth visits as they are brief patient-initiated communications with a health care practitioner and not limited to patients residing in rural areas. Medicare also started paying for similar virtual communications with clinicians at Rural Health Clinics and Federally Qualified home health care providers, expanding access to care for patients in underserved rural areas.

And starting in 2020, Medicare separately has paid clinicians for e-visits, which are non-face-to-face, patient-initiated communications through an online patient portal. These types of services don’t require Medicare patients to go to the doctor’s office and are available in all types of locations including the patient’s home, and in all areas of the country (not just rural areas). Beneficiaries need to have an established or existing relationship with their Home Health Care Service provider to get these virtual services.

Similarly, CMS implemented statutory changes enacted by Congress so that Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have the flexibility to offer innovative telehealth services as part of their basic benefit, expanding access to the latest telehealth technologies for MA enrollees. In 2020, over half of all plans are offering these additional telehealth benefits, reaching approximately up to13.7 million Medicare Advantage enrollees.

Expanding Telemedicine For Medicare Beneficiaries During The COVID-19 Outbreak

CMS’s efforts to expand telehealth prior to the COVID-19 public health emergency served as a strong foundation for action in the early days of the pandemic. One of the first steps CMS took in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency was to temporarily expand the scope of Medicare telehealth to allow Medicare beneficiaries across the country—not just in rural areas—to receive telehealth services from any location, including their homes. CMS also added 135 allowable services, more than doubling the number of services that beneficiaries could receive via telehealth. Examples include emergency department visits, initial nursing facility and discharge visits, home visits, and physical, occupational and speech therapy services. Medicare also ensured that Home Health Care Service providers like physicians were paid for these telehealth services at the same payment rate as they would receive for in-person services. Additionally, CMS is allowing telehealth technology to fulfill many requirements for clinicians to see their patients face-to-face in different health care settings, including inpatient rehabilitation facilities, hospice, and home health.

CMS has temporarily expanded the types of Home Health Care Service providers that can offer telehealth to broaden patient access to care. Outside of the public health emergency, only doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certain other types of practitioners could deliver telehealth services. During the emergency, a wider range of practitioners can provide telehealth services, including physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologists. Additionally, for the first time, through temporary authority added by the CARES Act, CMS is able to pay Rural Health Clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers to provide telehealth services, giving Medicare beneficiaries located in rural and other medically underserved areas more options to access care from their home without having to travel.

The Trump Administration has also removed other barriers that may limit beneficiary access to telehealth services. Usually, interactive audio-video technology is required for telehealth visits. This can be a challenge for beneficiaries; often, they either don’t have access to the technology or choose not to use it even if offered by their practitioner. At the beginning of the public health emergency, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Civil Rights announced that it would exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for HIPAA violations against Home Health Care Service providers that serve patients in good faith through everyday communications technologies, such as FaceTime or Skype, during the emergency. Soon after, CMS went even further to eliminate these barriers by paying for certain telephone evaluation and management visits and behavioral health services, and paying practitioners at the same rate as similar in-person services.

In addition, HHS Office of Inspector General announced that it would not enforce requirements for practitioners to collect copayments from patients for these kinds of services.

Unprecedented Increases In Telemedicine

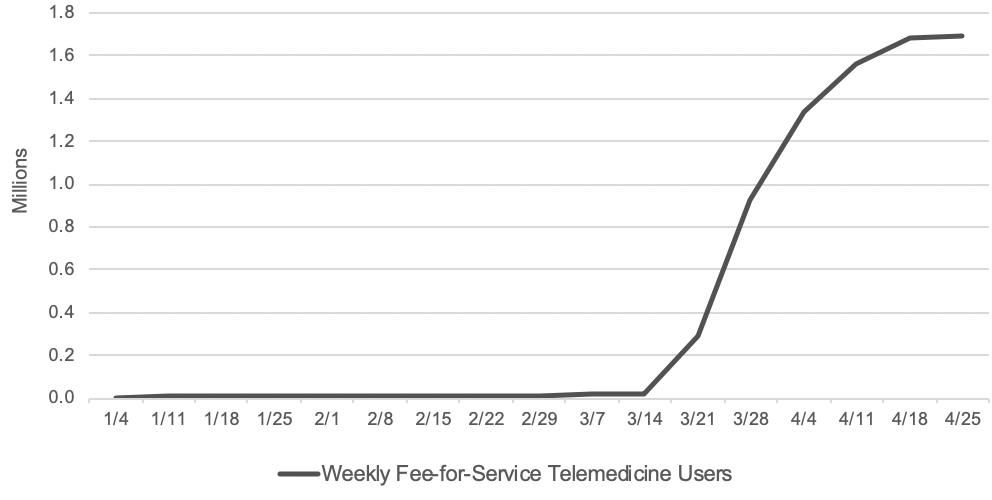

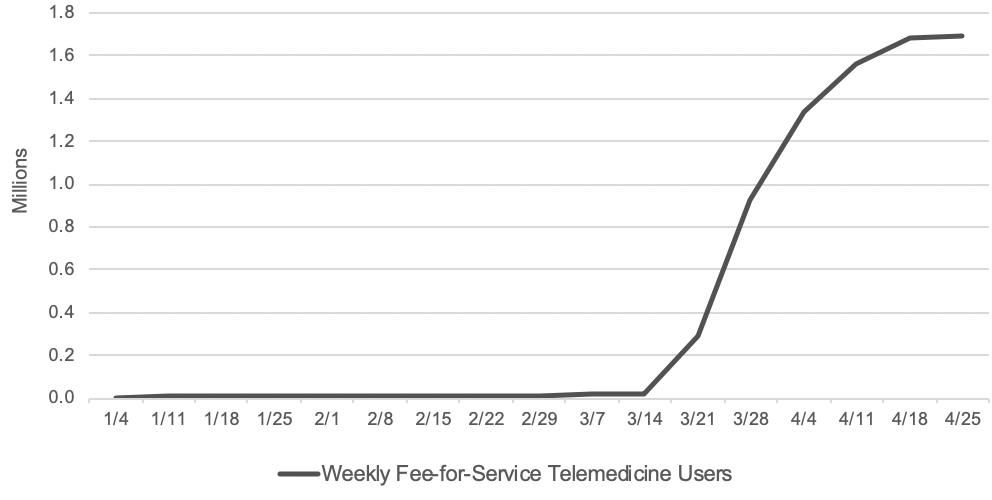

With wide-ranging telemedicine flexibilities, there has been a surge in the number of beneficiaries getting telemedicine services. Before the public health emergency, approximately 13,000 beneficiaries in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare received telemedicine in a week. In the last week of April, nearly 1.7 million beneficiaries received telehealth services.

In total, over 9 million beneficiaries have received a telehealth service during the public health emergency, mid-March through mid-June. Specifically, data points presented in this section of the post are from internal CMS analysis of Medicare FFS claims data from March 17through June 13, 2020 (using data processed through June 19, 2020). Telemedicine services include services on the Medicare telehealth list including audio-only visits, as well as virtual check-ins and e-visits.

According to Medicare FFS claims data, beneficiaries, regardless of whether they live in a rural or urban area, are seeking care during the pandemic through telemedicine services. In rural areas, 22 percent of beneficiaries used telehealth services, and 30 percent of beneficiaries in urban areas did so. There has been regional variation in use of telemedicine during the pandemic. For example, beneficiaries in northeastern states—New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island and Massachusetts—have a higher percentage of telemedicine services (over 35 percent of beneficiaries in those states received a telehealth service) compared to those in states in the north central part of the country—South Dakota, Nebraska, North Dakota, Montana and Idaho (less than 17 percent of beneficiaries in those states received a telehealth service). The regional variation could be due to the extent to which Home Health Care Service providers in those states offered telemedicine services and whether patients sought out care via that option.

Beneficiaries are getting care through telemedicine during the pandemic at similar rates across demographics. For example, 30 percent of female beneficiaries and 25 percent of male beneficiaries have received telemedicine services during the COVID-19 public health emergency to date. Across all age groups, 25-34 percent of beneficiaries have received a telemedicine service (34 percent among beneficiaries below the age of 65, 25 percent among beneficiaries between ages 65-74, 29 percent among beneficiaries between ages 75-84, and 28 percent among beneficiaries older than 85). There are also no significant differences by race or ethnicity among beneficiaries who received telemedicine services (25 percent among Asians, 29 percent among Blacks, 27 percent among Hispanics, 28 percent among Whites, and 26 percent among others).

Dually eligible beneficiaries (low-income beneficiaries that qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid) have had higher rates of telemedicine use: 34 percent of dually eligible beneficiaries have had a telemedicine service, compared to 26 percent of Medicare-only beneficiaries. Even among dually eligible beneficiaries, there are no significant differences across race or ethnicity groups (30 percent among Asians, 34 percent among Blacks, 33 percent among Hispanics, 35 percent among Whites, and 31 percent among others).

Evaluation and management (E/M) visits, or office visits, have been the most common form of telehealth, with nearly 5.8 million beneficiaries receiving an E/M telehealth visit since the public health emergency started. Additionally, 38 percent of beneficiaries who had an E/M visit furnished during the public health emergency did so via telehealth. Another area where telehealth has been used frequently has been mental health services with a psychiatrist or psychologist: approximately 460,000 beneficiaries (or 60 percent) receiving this care through telehealth. Telehealth for mental health care is showing great promise for our Medicare beneficiary population, who may otherwise have felt stigmatized seeking out care in-person.

Additionally, during the pandemic, CMS expanded the availability of telehealth services in other settings of care, including nursing homes, where beneficiaries may be particularly vulnerable. We found that 26 percent of beneficiaries who received nursing home visits did so by telehealth. Lastly, nearly 1.5 million beneficiaries have been able to access preventive health services during this time, and 19 percent of those beneficiaries received such services by telehealth.

The use of audio-only telehealth services has also been shown to be helpful for the Medicare population during the public health emergency, as many patients may not have access to or feel comfortable using video technology. Over 3 million beneficiaries have received telehealth services via traditional telephone. That means nearly one-third of beneficiaries that received a telemedicine service did so using audio-only telephone technology.

The claims data are preliminary since Home Health Care Service providers have 12 months after they furnish a service to submit their claims to CMS. But as exhibit 1 shows, the early data show a dramatically accelerated adoption of telehealth in a matter of months, which warrants consideration of which telehealth flexibilities should become a permanent part of the Medicare program.

Exhibit 1: Number of Medicare FFS beneficiaries receiving telemedicine per week

Source: Internal CMS analysis of Medicare FFS claims data, March 17, 2020 through June 13, 2020(using data processed through June, 19, 2020) Notes: Telemedicine is defined to include services on the Medicare telehealth list including audio-only visits, as well as virtual check-ins and e-visits.

Looking Ahead

Telehealth will never replace the gold-standard, in-person care. However, telehealth serves as an additional access point for patients, providing convenient care from their doctor and health care team and leveraging innovative technologies that could improve health outcomes and reduce overall health care spending. The rapid explosion in the number of telehealth visits has transformed the health care delivery system, raising the question of whether returning to the status quo turns back the clock on innovation.

The data have shown that telehealth can be an important source of care across the country, not just for those living in rural areas. Additionally, the immediate uptake in telehealth demonstrates the agility of the health care system to quickly scale up telehealth services, so that Home Health Care Service providers can safely take care of their patients while avoiding unnecessary exposure to the virus.

In light of our new experience with telehealth during this pandemic, CMS is reviewing the temporary changes we made and assessing which of these flexibilities should be made permanent through regulatory action. As part of our review, we are looking at the impact these changes have had on access to care, health outcomes, Medicare spending, and impact on the health care delivery system itself.

First, it is important to assess whether the mode of telehealth service delivery is clinically appropriate and safe for patients, as compared to an in-person visit. For example, during the public health emergency, CMS expanded certain telemedicine services to both new and established patients, where previously those services were limited to patients who had an established relationship with the practitioner. CMS took this action to make these services as widely available as possible given the need to reduce exposure risks for practitioners and patients. As the health care system enters a new normal, it is important to consider whether allowing people with particularly acute needs to be seen by a clinician for the first time via telemedicine, instead of in-person, will result in the best possible outcomes.

Second, we need to assess the Medicare payment rates for telehealth services. During the public health emergency, Medicare paid the same rate for a telehealth visit as it would have paid for an in-person visit, given the unique circumstances of the pandemic. Outside the pandemic, by law Medicare usually pays for telehealth services at rates similar to what professionals are paid in the hospital setting for similar services. Further analysis could be done to determine the level of resources involved in telehealth visits outside of a public health emergency, and to inform the extent to which payment rate adjustments might need to be made. For example, supply costs that are typically needed to enable safe in-person care (for, e.g., patient gowns, cleaning, or disinfectants) and built into the in-person payment rate are not needed in a telehealth visit. On the other hand, there are new processes that clinicians must create for telehealth visits, with associated costs.

Lastly, it is vital that beneficiaries and taxpayer dollars are protected from unscrupulous actors. As more Home Health Care Service providers use telehealth to treat beneficiaries, CMS is examining our data from many angles. We are monitoring program integrity implications such as practitioners who may be offering shorter telehealth visits with patients to maximize payment, or billing more visits than are possible in a day. We know the path forward to expanding telehealth relies on CMS addressing the potential for fraud and abuse in telehealth, as we do with all services.

During these unprecedented times, telemedicine has proven to be a lifeline for Home Health Care Service providers and patients. The rapid adoption of telemedicine among providers and patients has shown that telehealth is here to stay. CMS remains committed to ensuring that the government supports innovation in telehealth that leverages modern technology to enhance patient experience, providing more accessible care.

By Seema Verma | July 15, 2020

Source: Health Affairs

by M | Jul 18, 2020 | News |

In response to the COVID-19 emergency, the federal government distributed billions of dollars in CARES Act relief funding to Home Health Agencies, including Medicare-certified home health agencies.

In some cases, though, the funds are being held up due to the distribution process. That’s a costly hold-up for providers, many of which are using the relief funding as a financial lifeline to help mitigate COVID-19 costs and disruption.

Specifically, buyers that purchased health care companies in January found themselves placed on the backburner. In other words, a home health agencies that acquired a competitor in late 2019 may not have gotten CARES Act relief money tied to that business.

“I have several clients who did not receive those general fund payments,” Randy Glenn, an attorney at Austin, Texas-based law firm Glenn Rogers, told Home Health Care News. “They amount to about a half-million dollars on average, from what I’ve seen.”

In April, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sent a first tranche of CARES Act funds to providers directly based on 2019 Medicare reimbursements. The money was wired to the bank accounts associated with the taxpayer identification number (TIN) on record.

This meant that owners that took over Medicare licenses in late 2019, or early 2020, did not receive relief money. Instead, the funds automatically went to previous owners who no longer operated these companies.

Further complicating the issue, former owners are not permitted to send the money directly to new owners. HHS requirements stipulate that the funds must be returned to the federal government.

The funds are to be reallocated in the next round of distribution, which could take months or longer, according to Glenn.

“There’s no guarantee that these funds are ever going to find their way to these providers who assumed these Medicare contracts in late 2019, or early 2020,” he said.

While being placed in “Medicare purgatory” is largely a phenomenon that is taking place in the skilled nursing space, home health providers and other Medicare contractors are not immune, according to Glenn.

“I believe that this does impact all Medicare contractors,” he said. “This can happen to anyone who has a Medicare contract and is providing care under that contract.”

For home health providers dealing with the financial fallout of the public health emergency, waiting for the next round of relief fund distribution may prove difficult.

And providers that have not received funds are operating at a competitive disadvantage, according to Glenn.

Many providers have seen cost increases since the start of the COVID-19 emergency. The most obvious cost of doing business is the rising price tag on personal protective equipment (PPE).

Amedisys Inc. (Nasdaq: AMED), for example, reported $1 million in increased costs due to the public health emergency in the first quarter of 2020. The costs were associated with increased training expenses, quarantine pay and PPE.

Meanwhile, Chicago-based in-home care franchises company BrightStar Care acquired $2 million in PPE alone.

In April, Moorestown, New Jersey-based Bayada Home Health Care Home Health Care told HHCN that the company used a year’s worth of supplies in just one week. This led the company to launch a fundraising campaign for, among other things, supplies.

Additionally, several providers saw their bottom lines take a hit due to a decline in home health admissions.

Moving forward, Glenn believes that there is a clear path forward for HHS when it comes to solving the issue of misdirected funds.

“I believe this can be pretty quickly and easily solved,” Glenn said. “Someone at HHS who has the authority to take this on and see it through to the end [should] just dig into this and get the funds to the right place. HHS is under pressure because of COVID-19 and their resources are stretched, but there’s no doubt that this a pretty simple fix.”

By Joyce Famakinwa | July 15, 2020

Source: Home Health Care News

by M | Jul 16, 2020 | News |

Direct care workers are still undervalued, undertrained and have little opportunity for career advancement, according to a new report from PHI.

Ultimately, that’s bad for home-based care agencies — and their bottom lines.

New York-based PHI is a direct care worker and senior care advocacy organization. PHI typically classifies direct care workers as personal care aides, home health aides and nursing assistants, or more generally those who support seniors and individuals with disabilities.

“Quality care is [contingent upon] quality direct care workers,” Angelina Drake, PHI’s COO and the author of the report, told Home Health Care News. “They will deliver higher-quality care and contribute more meaningfully to the client’s health, safety and well-being if they are better paid, trained and supported.”

Among other findings, PHI found that the direct care workers suffer from inadequate training, a lack of outside understanding of the complexity of the work they do and a system that does not allow many opportunities for meaningful career movement.

One solution in regard to improved training: mandated federal training requirements, according to PHI. This already exists in home health care, as home health aides are required across the U.S. to undergo at least 75 hours of training.

In contrast, personal care aides have no federal requirements and are governed by a mixed bag of state laws and regulations.

PHI recommends that each direct care worker be trained to the point where they have a grasp on a set of core competencies. Broadly, that’s defined as having the skills, knowledge and abilities to complete one’s role.

“The report does conclude with a recommendation that there be a set of core competencies that underlie all direct care,” Drake said. “Once agreed upon and required for states to adopt these standards, they can then build additional training for roles that have greater responsibilities or more specialized responsibilities.”

No agreed upon requirements means that direct care workers’ capabilities look different across state lines, potentially hurting themselves as well as the seniors they’re serving, PHI argues. Workers should also be able to show that they are improving their skills during training — and not just hitting an hourly training threshold — before moving forward.

“Whether you are a personal care aide, home health aide or nursing assistant, there are core competencies that are really central to delivering quality care, and we need to at least ensure that those are in place,” Drake said. “We want competency-based training, which means that participants will need to show that they have acquired skills before they can move forward.”

Only about 60% of states have some sort of home care licensure requirements, according to the Home Care Association of America (HCAOA).

More regulation could help both agencies and direct care workers. Universal training for direct care workers will give them more confidence on the job, allow them to increase their capabilities and ideally get promoted, PHI claims.

That sort of room for improvement creates value for the workers and leads to better care, both of which benefit home care agencies.

“Turnover costs are some of the major expenses that long-term care providers face,” Drake said. “These can be improved by better preparation and job quality for the direct care workforce. And consumer satisfaction is another driver of business that can be improved by quality jobs.”

Other aspects of the direct care workers’ environment that have gone underappreciated are the physical, social and emotional demands, according to the report.

These, of course, have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis.

“Employers need to look at what they can do to improve job quality for direct care workers,” Drake said. “Employers are often limited in their ability to change the base wage for workers, but there are other things they can do to improve job quality to make this a better job all around. A really important piece of that is training.”

By Andrew Donlan | July 14, 2020

Source: Home Health Care News