by M | Jun 15, 2020 | News |

John Stagliano never was much of a hospital guy.

“Anytime he ever went was when something bad happened,” said his son, also named John Stagliano. “I guess he had that, ‘Nothing ever good is gonna be coming from there,’ kind of thing.”

That made it all the more difficult when the elder Stagliano contracted the novel coronavirus at the end of February. At 82, he was statistically at a high risk for the disease to become serious, and potentially fatal. But despite his children’s pleading, he would not be admitted to the hospital.

“He just didn’t want to be there,” said his son John.

So he got his father set up to receive fairly intensive care in the basement of the Exton home the elder Stagliano shares with his wife, Catherine Stagliano. A home health care team through Penn Medicine brought an oxygen machine down to what the family calls the “man cave” and set up an app so his kids could monitor their father’s heart rate, temperature and other vital signs remotely.

For about two weeks, Catherine Stagliano, also 82, trekked up and down the steps to the basement, bringing her husband food and caring for him in the man cave.

Until, predictably, she started feeling sick, too.

For older adults, staying healthy often involves rotating in and out of skilled nursing facilities after an injury, a fall, or a joint replacement surgery. Sometimes, those short-term stays become long-term ones, in the same facility.

If the Staglianos hadn’t made a fuss, they would have likely ended up receiving care in a hospital for COVID-19 and then been discharged to a skilled nursing facility once they were stable — the same facilities that have been ground zero for the coronavirus pandemic. In Pennsylvania, two-thirds of COVID-19 deaths have happened there.

As families watch nursing homes struggle to contain the virus, many have started to consider bringing health care for their loved ones into their own homes.

The trend isn’t new. As the baby boomer generation ages, hospital systems, government agencies and insurers have been shifting long-term care away from costly institutions and toward the home for at least a decade. Many experts predict that the risks posed by COVID-19 may accelerate that process, whether the system is ready for it or not.

Is telemedicine the ‘new normal’?

The pandemic is already shifting the day-to-day logistics of seeing a doctor.

As soon as models began to predict that hospital systems could be overwhelmed by a surge of COVID-19 patients, the federal Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services changed its policies surrounding telemedicine, allowing health systems to bill for remote appointments that previously would not have been eligible for reimbursement. That meant more people were able to receive care at home who would have otherwise created crowded hospitals and taken up valuable bed space.

At health systems around the Philadelphia region, doctors started treating more people virtually, at home, for a variety of illnesses, from addiction medicine to cancer treatment — as well as those with COVID-19, like the Staglianos.

“This situation … is shining a much brighter spotlight,” said David Baiada, CEO of Bayada Home Health Care, the largest long-term provider of at-home care in Pennsylvania. “It’s also creating innovation,” such as the remote monitoring of symptoms and increased use of telemedicine.

As people are discouraged from visiting the hospital for routine care, they’re also getting used to accessing it from home and could be more willing to keep doing so even after the pandemic lifts — especially if the loosened Medicare regulations remain in place.

“It’s going to be really hard to go back from that because now we’ve seen that it’s possible to do this and patients like getting telehealth and care at home,” Rachel Werner, head of the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard David Institute of Health Economics, said of the relaxed telehealth restrictions. “In the next year or two, I think we’re going to find that nursing homes are going to have to close because there just won’t be as much demand for the care that they provide. I think we’ve probably turned a corner on that.”

Penn Medicine went to such great lengths to keep people out of the hospital that by mid-May the numbers of patients being treated at home and in the hospital were roughly the same. Traditional care at home was supplemented with multiple telemedicine visits a day and a lot of communication with family members. Still, said Nina O’Connor, chief medical officer for Penn’s home health care, the model asks a lot of family caregivers.

“At-home care does depend on informal caregiving from family members or friends,” said O’Connor. Though loved ones may have had more time than usual during the pandemic as shutdowns rendered many jobless, there is no guarantee that will continue to make the model sustainable, she noted.

“That is a real barrier, one that we haven’t completely overcome,” she said.

John and Catherine Staglioni, both 82., pose for a photo during a trip to Key West over the Thanksgiving holiday. Both were treated for COVID-19 at home in Exton, Pa. (Provided by John Staglioni)

John Stagliano said he was grateful his parents could remain at home, but he ultimately would have preferred if they had been in a setting where they had 24/7 monitoring.

“If they’re OK, the home care’s fine,” he said. “However, if they start not being able to take care of one another, then it becomes a problem. And all the home health care’s not gonna help you with that.”

While both parents were sick, Stagliano moved from his home in Reading to stay with his brother who lives nearby, so he could make the 10-minute drive to their house if necessary. He is able to work from home, so he had some flexibility. Even so, the care took a toll.

“My stress level was ridiculous,” Stagliano said.

Financial tides have begun to turn

Though the bulk of the residents at any given nursing home may be there for the long term, it’s the patients discharged from the hospital to recover after operations like joint replacements, or short-term illness like COVID-19, that come with higher reimbursement rates. Many nursing homes subsidize the care of their long-term patients through those short-term patients, who stay for just a few weeks.

The operations of nursing homes depend on both streams of patients, but the risks posed by COVID-19 could change both for the foreseeable future.

The notion of shifting more elder care into the home was brewing long before the coronavirus tore through nursing facilities. By 2050, the U.S. population over age 65 is expected to be nearly double what it was in 2012. Pennsylvania is particularly old, with 19% of its population over 65, compared to the national median of 14%.

“There are a lot of old people coming here soon, and we’re gonna have to figure out what to do with that and how to pay for it,” said Kirstin Manges, a national clinician scholar who studies post-acute care for older adults and a registered nurse by training.

Because of the anticipated rising costs that come with caring for more older adults, government officials and health system operators have been thinking about how to reduce the costs of elder care for more than a decade. Plus, people overwhelmingly want to stay at home.

“People express the desire to be able to age in place as much as possible, in their homes and in their communities,” said Kevin Hancock, deputy secretary of the state Department of Human Services’ Office of Long-Term Living. “That view has underwritten the development of long-term care services really for about the last 25 years.”

However, Medicaid-funded care through Social Security was initially set up to pay for nursing home stays, not care in the community.

Nationally, 87% of state Medicaid spending on long-term care went to nursing homes in 1990, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

That started to shift after the passage of Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. Lobbyists and advocates continuously made the point that home care is safer, more humane and more cost-effective than institutionalized long-term care.

The industry has adapted to challenges: Stymied by a limited stock of ADA-compliant housing, home health and government agencies have expanded their scope to focus on housing development, too. Philadelphia-based Liberty Resources has built 103 units through its own development arm, and priority is given to individuals transitioning out of nursing home care.

Pennsylvania has come a long way. By 2018, the state Department of Human Services had launched Community Health Choices, a program to codify and streamline community care for people with disabilities over age 21 and seniors who received Medicaid. The state also has a department dedicated to transitioning individuals out of nursing home care into their homes.

In Pennsylvania, 62% of the people now drawing those federal funds for long-term care receive that care outside of a nursing home. The funding is now split around 50-50, between institutional and community-based care.

Preliminary numbers for January through April of this year do not show an increase in the number of people moving out of institutional settings compared to previous years, so it’s too soon to know whether the pandemic will accelerate that shift.

By Nina Feldman, Laura Benshoff | June 12, 2020

Source: WHYY

by M | Jun 13, 2020 | News |

The Patient-Driven Groupings Model (PDGM) and its unintended ripple effects were supposed to be the dominant story this year for the nation’s 12,000 or so Medicare-certified home health care providers. But the coronavirus has rewritten the script for 2020, throwing most of the industry’s previous projections out the window.

While PDGM — implemented on Jan. 1 — will still shape home health care’s immediate future, several other long-term trends have emerged as a result of the coronavirus and its impact on the U.S. health care system.

These trends include unexpected consolidation drivers and the sudden embrace of telehealth technology, the latter of which is a development that will affect home health providers in ways both profoundly positive and negative. Unforeseen, long-term trends will also likely include drastic overhauls to the Medicare Home Health Benefit, a revival of SNF-to-home diversion and more.

Now that providers have had roughly three full months to adapt to the coronavirus and transition out of crisis mode, Home Health Care News is looking ahead to what the industry can expect for the rest of 2020 and beyond.

‘Historic’ consolidation will still happen, with some unexpected drivers

Although the precise extent was often up for debate, most industry insiders predicted some level of consolidation in 2020, driven by PDGM, the phasing out of Requests for Anticipated Payment (RAPs) and other factors.

That certainly appeared to be true early on in the year, with Amedisys Inc. (Nasdaq: AMED), LHC Group Inc. (Nasdaq: LHCG) and other home health giants reporting more inbound calls related to acquisition opportunities or takeovers of financially distressed agencies.

In fact, during a fourth-quarter earnings call, LHC Group CEO and Chairman Keith Myers suggested that 2020 would kick off a “historic” consolidation wave that would last several years.

“As a result of this transition in Q4 and the first few months of 2020, we have seen an increase in the number of inbound calls from smaller agencies looking to exit the business,” Myers said on the call. “Some of these opportunities could be good acquisition candidates, and others we can naturally roll into our organic growth through market-share gains.”

Most of those calls stopped with the coronavirus, however.

Although the vast majority of home health agencies have experienced a decline in overall revenues during the current public health emergency, many have been able to compensate for losses thanks to the federal government’s multi-faceted response.

For some, that has meant taking advantage of the approximately $1.7 billion the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has distributed through its advanced and accelerated payment programs. For others, it has meant accepting the somewhat murky financial relief sent their way under the Provider Relief Fund.

In addition to those two possible sources of financial assistance, all Medicare-certified home health agencies have benefitted from Congress’s move to suspend the 2% Medicare sequestration until Dec. 31.

Eventually, those coronavirus lifelines and others will be pulled back, kickstarting M&A activity once again.

“We believe that a lot of the support has stopped or postponed the shakeout that’s occurring in home health — or that we anticipated would be occurring around this time,” Amedisys CEO and President Paul Kusserow said in March. “We don’t believe it’s over, though.”

Not only will consolidation happen, but some of it will be fueled by unexpected players.

With the suspension of elective surgeries and procedures, hospitals and health systems have lost billions of dollars. Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association (AHA), estimated that hospitals are losing as much as $50 billion a month during the coronavirus.

“I think it’s fair to say that hospitals are facing perhaps the greatest challenge that they have ever faced in their history,” Pollack, whose organization represents the interests of nearly 5,000 hospitals, told NPR.

To cut costs, some hospitals may look to get rid of their in-house home health divisions. It’s a trend that may already be happening, too.

The Home Health Benefit will look drastically different

With a mix of temporary and permanent regulatory changes, including a redefinition of the term “homebound,” the Medicare Home Health Benefit already looks very different now than it did three months ago. But the benefit will likely go through further retooling in the not-too-distant future.

Broadly, the Medicare Part A Trust Fund finances key services for beneficiaries.

While vital to the national health care infrastructure, the fund is going broke — and fast. In the most recent CMS Office of the Actuary report released in April, the Trust Fund was projected to be entirely depleted by 2026.

The COVID-19 virus has only accelerated the drain on the fund, with some predicting it to run out of money two years earlier than anticipated. A group of health care economics experts from Harvard and MIT wrote about the very topic on a joint Health Affairs op-ed published Wednesday.

“COVID-19 is causing the Medicare Part A program and the Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund to contend with large reductions in revenues due to increased unemployment, reductions in salaries, shifts to part-time employment from full time and a reduction in labor force participation,” the group wrote. “In addition to revenue declines, there was a 20% increase in payments to hospitals for COVID-related care and elimination of cost sharing associated with treatment of COVID.”

Besides those and other cost pressures, Medicare is simultaneously expanding by about 10,000 new people every day. The worst-case scenario: the Medicare Part A Trust Fund goes broke closer to 2024.

There are numerous policy actions that can be taken to reduce the financial strain on the trust fund. In their op-ed, for example, the team of Harvard and MIT researchers suggested shifting all of home health care under Part B.

In 2018, Medicare spent about $17.9 billion on home health benefits, with roughly 66% of that falling under Part B, which typically includes community-based care that isn’t linked to hospital or nursing home discharge. Consolidating all of home health care into Part B would move billions of dollars away from Part A, in turn expanding the Trust Fund’s lifecycle.

“Such a policy change would move nearly $6 billion in spending away from the Part A HI Trust Fund but would put upward pressure on the Part B premium,” the researchers noted.

Of course, all post-acute care services may still undergo a transformation into a unified payment model one day. However, the coronavirus has devastated skilled nursing facility (SNF) operators, who were already dealing with the Patient-Driven Payment Model (PDPM), a payment overhaul of their own.

Regulators may shy away from introducing further disruption until SNFs have a chance to recover, a process likely to take years — if not decades.

Previously, the Trump administration had estimated that a unified payment system based on patients’ clinical needs rather than site of care would save a projected $101.5 billion from 2021 to 2030.

Telehealth will be a double-edged sword

The move toward telehealth was a long-term trend that home health providers were cognizant of before COVID-19, even if some clinicians were personally skeptical of virtual visits. But because the virus has demanded social distancing, telehealth has forced its way into health care in a manner that would have been almost unimaginable in 2019.

In late April, during a White House Coronavirus Task Force briefing, President Donald Trump indicated that the number of patients using telehealth had increased from about 11,000 per week to more than 650,000 people per week.

Meanwhile, MedStar Health went from delivering just 10 telehealth visits per week to nearly 4,000 per day.

Backed by policymakers, technology companies and consumers, telehealth is likely here to stay.

“I think the genie’s out of the bottle on this one,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in April. “I think it’s fair to say that the advent of telehealth has been just completely accelerated, that it’s taken this crisis to push us to a new frontier, but there’s absolutely no going back.”

The telehealth boom could mean improved patient outcomes and new lines of business for home health providers. But it could also mean more competition moving forward.

For telehealth to be a true game-changer for home health providers, Congress and CMS would need to pave the way for direct reimbursement. Currently, a home health provider cannot get paid for delivering virtual visits in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) has floated the idea of introducing legislation that would allow for direct telehealth reimbursement in the home health space, but, so far, no concrete steps have been taken — at least in public. With a hyper-polarized Congress and a long list of other national priorities taking up the spotlight, it’s impossible to guess whether home health telehealth reimbursement will actually happen.

While home health providers can’t directly bill for in-home telehealth visits, hospitals and certain health care practitioners can. That regulatory imbalance could lead to providers being used less frequently as “the eyes and ears in the home,” some believe.

A new SNF-to-home diversion wave will emerge

Over the past two decades, many home health providers have been able to expand their patient census by poaching patients from SNFs. Often referred to as SNF-to-home diversion, the approach didn’t just benefit home health providers, though. It helped cut national health care spending by shifting care into lower-cost settings.

At first, the stream of SNF residents being shifted into home health care was like water being shot from a firehose: In 2009, there were 1,808 SNF days per 1,000 FFS Medicare beneficiaries, a March 2018 analysis from consulting firm Avalere Health found. By 2016, that number plummeted to 1,539 days per 1,000 beneficiaries — a 15% drop.

In recent years, that steady stream has turned into a slow trickle, with more patients being sent to home health care right off the bat. In the first quarter of 2019, 23.3% of in-patient hospital discharges were coded for home health care, while 21.1% were coded for SNFs, according to data from analytics and metrics firm Trella Health.

Genesis HealthCare (NYSE: KEN) CEO George Hager suggested the initial SNF-to-home diversion wave was over in March 2019. Kennett Square, Pennsylvania-based Genesis is a holding company with subsidiaries that operate hundreds of skilled nursing centers across the country.

“To anyone [who] would want [to] or has toured a skilled nursing asset, I would challenge you to look at the patients in our building and find patients that could be cared for in a home-based or community-based setting,” Hager said during a presentation at the Barclays Global Healthcare Conference. “The acuity levels of an average patient in a skilled nursing center have increased dramatically.”

Yet that was all before the coronavirus.

Over the last three months, more than 40,600 long-term care residents and workers have died as a result of COVID-19, according to an analysis of state data gathered by USA Today. That’s about 40% of the U.S.’s overall death toll.

CMS statistics place that number closer to 26,000.

In light of those figures and infection-control issues in congregate settings, home health providers will see a new wave of SNF-to-home diversion as robust as the first. As the new diversion wave happens, providers will need to be prepared to care for patients with higher acuity levels and more co-morbidities.

“[That’s going to change] the psyche of the way people are going to view SNFs and long-term care facilities for the rest of our generation,” Bruce Greenstein, LHC Group’s chief strategy and innovation officer, said during a June presentation at the Jefferies Virtual Healthcare Conference. “You would never want to put your parent in a facility if you don’t have to. You want options now.”

One stat to back up this idea: Over 50% of family members are now more likely to choose in-home care for their loved ones than they were prior to the coronavirus, according to a survey from health care research and consulting firm Transcend Strategy Group.

Separate from SNF-to-home diversion, hospital-to-home models will also likely continue to gain momentum after the coronavirus.

There will be a land grab for palliative care

Over the past two years, home health providers have aggressively looked to expand into hospice care, partly due to the space’s relatively stable reimbursement landscape. Amedisys — now one of the largest hospice providers in the U.S. — is the prime example of that.

During the COVID-19 crisis, palliative care has gained greater awareness. Generally, palliative care is specialized care for people living with advanced, serious illnesses.

“Right now, we are seeing from our hospital partners and our community colleagues the importance of palliative care, including advanced care as well as appropriate pain and symptom management,” Capital Caring Chief Medical Officer Dr. Matthew Kestenbaum previously told HHCN. “The number of palliative care consults we’re being asked to perform in the hospitals and in the community has actually increased. The importance of palliative care is absolutely being shown during this pandemic.”

As community-based palliative care programs continue to prove their mettle amid the coronavirus, home health providers will increasingly consider expanding into the market to further diversify their services.

Currently, just 10% of community-based palliative care programs are operated by home health agencies.

Demand will reach an all-time high

The home health industry may ultimately shrink in terms of raw number of agencies, but the overall size of the market is very likely to expand at a faster-than-anticipated pace.

In years to come, home health providers will still ride the macro-level tailwinds of an aging U.S. population with a proven preference to age in place — that hasn’t changed. But because of SNF-to-home diversion and calls to decentralize the health care system with home- and community-based care, providers will see an increase in referrals from a variety of sources.

In turn, home health agencies will need to ramp up their recruitment and retention strategies.

There’s already early evidence of this happening.

Last week, in St. Louis, Missouri, four home-based care agencies announced that they were hiring a combined 1,000 new employees to meet the surge in demand, according to the St. Louis Dispatch.

Meanwhile, Brookdale Senior Living Inc. (NYSE: BKD) similarly announced plans to hire 4,500 health care workers, with 10% of those hires coming from the senior living operator’s health care services segment.

Bayada Home Health Care likewise announced plans to ramp up hiring.

“We are absolutely hiring more people now than ever,” Bayada CEO David Baiada previously told HHCN. “The need for services — both because of societal and demographic evolution, but also because of what we anticipate as a rebound and an increase in the demand for home- and community-based care delivery as a result of the pandemic — is requiring us to continue to accelerate our recruitment efforts.”

The bottom line: The coronavirus may have presented immediate obstacles for home health providers, but the long-term outlook is brighter than ever.

By Robert Holly | June 10, 2020

Source: Home Health Care News

by M | Jun 11, 2020 | News |

The COVID-19 pandemic has ushered in a new era of telehealth for primary care, and patient-centered care is now easier than ever. This has been the model promoted as early as 1967 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The idea is that the patient and not the physician or the hospital is at the center of a wheel. Each health provider in the care team, including preventive, acute, and chronic care, is at the end of a spoke in the wheel. Each provider contributes to the care of the patient, but the patient is the ultimate decision-maker. Data shows that chronic medical conditions are managed better in this model.

Why isn’t patient-centered care just standard of care? One of the major barriers is how we have traditionally paid for health care: Under the fee-for-service model, the provider only received payment for a procedure or visit. But patient-centered care requires many time-consuming duties that are not patient visits, such as reviewing the medical record, reading and responding to email and phone calls, and monitoring tests. Under the fee for service model, those activities were not compensated.

The transition from fee-for-service to a more integrated form of patient compensation has been much too slow. As a result, physicians have been incentivized to fill their schedule with office visits. Many of these visits are not needed; they benefit physicians and the health care facility more than patients. Now that telehealth visits are being reimbursed at close to or equal to what office visits were, we can come closer to putting the patient at the center

A few years ago, at my hospital, the department of general medicine switched from fee-for-service to a “panel-based” model to compensate their primary care physicians. That means primary care physicians are now paid a fee per patient rather than per visit or procedure. My job is to manage my panel of patients and not to fill my schedule. For example, I get paid the same whether I manage a patient’s diabetes via the phone or in person. If I get an email from a patient with a question about their glucose monitoring regimen, it’s part of my job to answer. Under fee-for-service, I might spend 30 minutes answering that email without any compensation.

The old system incentivized my staff to call that patient into the office for a visit they may not really need just so I could get paid. Now, the incentive is to make contact based on patients’ preference and clinical need rather than physician need. With the panel management model, the financial interest of physicians is aligned with the patient’s health: the incentive is on what is necessary, not just what is doable.

We needed telemedicine before COVID, but the virus made it clear just how much and how quickly. Due to overwhelming need and demand, many of the old barriers to reimbursement have been lowered or eliminated. CMS and commercial insurance companies have issued policy changes expanding coverage and access so patients can get their care while staying at home. Health care systems have rapidly expanded the technological infrastructure to integrate telehealth with electronic health records. Additionally, many states are waiving in-state licensure requirements, allowing patients to “see” providers out of state. With this change, providers in Boston are now able to practice telemedicine for those who live outside Massachusetts and get paid at the same rate.

Telehealth won’t eliminate every barrier to patient-centered care. Many physicians are still skeptical about changes. They were trained in an era when the physician alone cared for the patient — some fear to lose the unique patient-doctor bond when other team members are involved in the care. The team approach requires patients to trust other physicians besides their own and be comfortable sharing sensitive and personal information with team members. As an ‘old school’ primary care physician in practice for 25 years, I was a late adapter to team care and telehealth. But I was always a proponent of patient-centered care. Now I see how interconnected they are.

As medical care is now more complex and fragmented, I have come to realize that team care is the best way to care for our patients because they have better access to us. For example, they can see a nurse practitioner instead of me with shorter waiting times. Furthermore, a nurse, social worker, case manager, mental health ‘coach’ or collaborator can more effectively educate patients, provide access to behavioral health services, and give tips on self-management support. I see physicians in my practice draws on the expertise of a variety of provider-team members. In sum, everyone gets more of what they need.

The recent changes in regulations in telehealth reimbursement need to be made permanent. Physicians should not be financially penalized for doing what is best for the patient. The old fee for service model is clearly not working: despite leading the world in medical expenditure, we are at the bottom on many health measures when compared with other advanced countries.

Our health care system, led by Centers by Medicare and Medicaid Services, needs to instead incentivize quality, improved outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Paying for telehealth and promoting non-face to face visits is one small step in practicing patient-centered care. Putting our patients first should not only be a slogan but a true mandate.

By Dr. Li Tso, opinion contributor — 06/09/20 11:00 AM EDT

Source: The Hill

by M | Jun 10, 2020 | News |

Across the country, just 10% of community-based palliative care programs are spearheaded by home health care providers. The coronavirus may change that moving forward.

As of Monday, there have been more 1.9 million confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States, with many individuals in recovery. But while some see a return to full health, doctors are also starting to notice a growing list of lasting health impacts, including heart, kidney and brain problems.

If secondary and tertiary complications prove common and long-lasting, that may lead to higher demand for advanced illness care, particularly for the senior population. It’s a trend that Capital Caring is already seeing, Dr. Matthew Kestenbaum, the organization’s chief medical officer, told Home Health Care News.

“Right now, we are seeing from our hospital partners and our community colleagues the importance of palliative care, including advanced care as well as appropriate pain and symptom management,” Kestenbaum said. “The number of palliative care consults we’re being asked to perform in the hospitals and in the community has actually increased. The importance of palliative care is absolutely being shown during this pandemic.”

Falls Church, Virginia-based Capital Caring is one of the largest nonprofit providers of advanced illness, hospice and at-home care for seniors in the Mid-Atlantic region. As one of the country’s original hospice demonstration sites, the company cut its teeth in end-of-life care but has since expanded into various services aimed at aging in place.

Overall, Capital Caring helps treat more than 2,000 people on a daily business across its services lines.

“We have really expanded our services after originally starting out as a hospice program,” Capital Caring President and CEO Tom Koutsoumpas told HHCN. “Our goal is to continue providing care across the continuum in order to help people stay at home. Whether that’s providing advanced illness care [or] home-based primary care — we’re doing whatever we can do to help individuals age in place.”

In addition to his CEO role at Capital Caring, Koutsoumpas is also the co-founder of both the Coalition to Transform Advanced Care (C-TAC) and the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation (NPHI).

Palliative and advanced illness care have arguably never been more in the spotlight than during the current public health emergency.

In fact, one recent op-ed in the Journal of Cardiopulmonary and Acute Care argues that palliative care principles should guide the care that all COVID-19 patients receive.

Broadly, the core aspects of palliative care can provide a foundation for responding to COVID-patient needs, including symptoms alleviation, multidisciplinary teams, patient-centered care and family support.

Capital Caring has been working to strengthen those core principles across its markets.

“We … have been very willing to work with our community partners, in terms of helping to guide symptom management, grief and loss counseling — not only for families of patients who have died from COVID, but for staff who’ve been taking care of them who are just not used to this degree of acuity or loss,” Kestenbaum said.

On its end, Capital Caring started closely following the coronavirus situation in February, then took action in the beginning of March. Its early response strategy included the formation of a dedicated leadership team focused on developing best practices and protocols.

The company also acted quickly to secure as much personal protective equipment (PPE) as possible while simultaneously shifting operations to virtual platforms.

“We’re using Zoom [for virtual meetings],” Kestenbaum said. “We considered a couple options, but … we were able to get that in place in a matter of two or three days. By the third week in March, all hospice team meetings were virtual. Only necessary home visits were being made — and we still did those very quickly.”

Nationally, 33% of palliative care programs are operated by hospice providers, 32% by hospitals, 14% by office practices or clinics, 11% by long-term care facilities and 10% by home health agencies, according to a 2019 report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC).

If home health providers don’t have experience in advanced illness or palliative care, they should turn to organizations like Capital Caring for support, Koutsoumpas said.

“Partnering with hospice and palliative care providers in the community is important,” he said. “Encouraging these kinds of relationships can really expand the ability to care for people in the community.”

A handful of home-based care providers have already signaled plans to expand into palliative care.

CareCentrix — a care management company that focuses on home-based care — announced in May it had acquired palliative care company Turn-Key Health for an undisclosed sum.

Paul Kusserow, president and CEO of Amedisys Inc. (Nasdaq: AMED), also recently hinted that palliative care may be in his company’s future.

“We’re primarily in home health and hospice now, but we’re moving forward into personal care and expanding into palliative care, which we believe is becoming increasingly important,” Kusserow previously told HHCN.

By Robert Holly | June 8, 2020

Source: Home Health Care News

by M | Jun 6, 2020 | News |

For seniors recovering from the coronavirus, home health care aides have provided another way to care for at risk adults that might otherwise need to be in a nursing home or adult care facility.

Both Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill De Blasio have called for an increase in home care to help keep seniors out of the hospital and even help slow the spread of the virus in nursing homes.

What You Need To Know

o Home health aides need more support.

o Older New Yorkers are especially vulnerable to COVID.

o Home health aides themselves have also died.

o Home health aides’s work can help free up needed hospital space.

“If I were advising a friend, I would say: You have a vulnerable person. Best to keep them at home and not put them in a congregate facility,” Cuomo said during an interview on MSNBC. “Keep them in a situation where you have the most control and that is the blunt truth.”

But home health care aides have not been left untouched by the virus.

A survey of six home care agencies showed that 780 home health care aides caught COVID-19 and 33 home aides have died.

However, these six agencies were also able to take care of 20,000 at risk adults during the past few months, keeping them home and out of the hospital system.

“By discharging them from the hospital, back home and skipping the step of the nursing home or rehab has really saved, I think, countless lives,” siad Michael Arnella, RN, the director of Clinical Services at Accent Care.

Arnella continued, “And then with the hospitals around 80% COVID at one point, having these other patients go in with DHS, DOPD, diabetes, would overwhelm the system. Home care plays a vital role in any type of emergency situation.”

By Morgan McKayNew York State

PUBLISHED 5:27 AM ET Jun. 02, 2020

Source: Spectrum News

by M | Jun 3, 2020 | Blog, News |

The COVID-19 pandemic and killing of George Floyd along with other recent deaths of African American people at the hands of police have laid bare stark structural and systemic racial inequities and their impacts on the health and well-being of individuals and communities. While these events have brought health and health care disparities into sharp focus for the media and public, they are not new. These longstanding and persistent health disparities are symptoms of broader social and economic challenges that are rooted in structural and systemic barriers across sectors — including housing, education, employment, and the justice system — as well as underlying racism and discrimination. Amid this difficult time for our nation, the increased recognition and understanding of disparities could provide a catalyst for the challenging work required to address them.

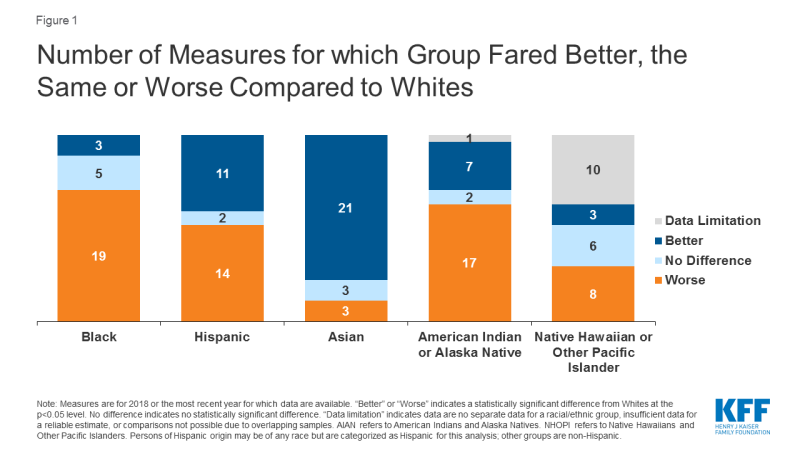

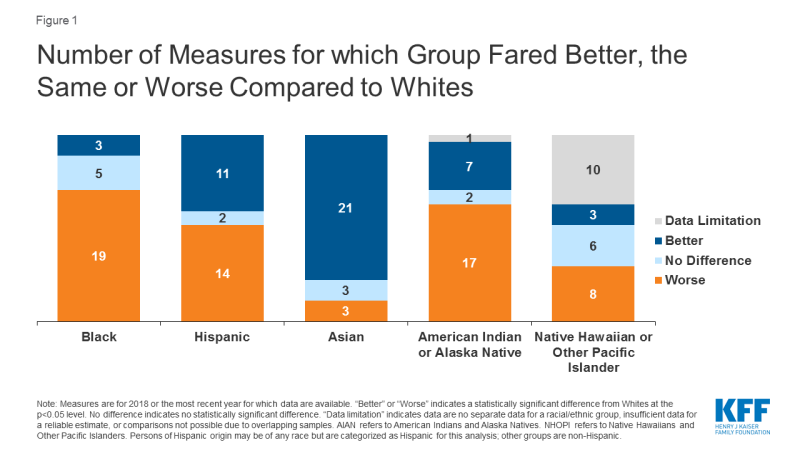

Despite being recognized and documented for many years, disparities in health and health care have persisted and in some cases widened over time. Our analysis finds that Black and American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) individuals continue to fare worse compared to White individuals across most examined measures of health status, including physical and mental health status; birth risks; infant mortality rates; HIV and AIDS diagnosis and death rates; and prevalence of and death rates due to certain chronic conditions (Figure 1). For example, the infant mortality rate for Black and AIAN individuals is roughly two times higher than the rate for White individuals. Black teens and adults have an over eight times higher HIV diagnosis rate and a nearly ten times higher AIDS diagnosis rate compared to their White counterparts; the HIV and AIDS diagnosis rates for Hispanic teens and adults are more than three times higher compared to the rates for those who are White.

Figure 1: Number of Measures for which Group Fared Better, the Same or Worse Compared to Whites

The disparate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people of color mirror and compound these broader underlying racial/ethnic disparities in health. Data across states show that, in the majority of states reporting data, Black people account for a higher share of COVID-19-related deaths and cases compared to their share of the population. Similarly, Hispanic individuals make up a higher share of confirmed cases relative to their share of the population in most states reporting data, and there have been striking disproportionate impacts for American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander people in some states. The resulting economic crisis has also had an unequal effect on people of color.

Health disparities, including disparities related to COVID-19, are symptoms of broader underlying social and economic inequities that reflect structural and systemic barriers and biases across sectors. Though health care is essential to health, it is a relatively weak health determinant. Research shows that social determinants of health—the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age—are primary drivers of health. They include factors like socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care (Figure 2). For example, children born to parents who have not completed high school are more likely to live in an environment that poses barriers to health such as lack of safety, exposed garbage, and substandard housing. They also are less likely to have access to sidewalks, parks or playgrounds, recreation centers, or a library. Further, evidence shows that stress negatively affects health across the lifespan and that environmental factors may have multi-generational impacts.

Figure 2: Social and Economic Factors Drive Health Outcomes

The heightened focus on and understanding of disparities can serve as a catalyst for the challenging work required to address them. Steps can be taken within the health care system that would help address health disparities. For example, actions to expand health coverage, such as adoption of the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults in the 14 states that have not yet expanded; increasing accessibility to health care providers; increasing access to linguistically and culturally appropriate care; and diversifying the health care workforce could help reduce health disparities. However, efforts to address health disparities also require cross-sector approaches beyond health care to affect the broader social and economic factors driving health. For example, actions to increase access to healthy food options and improve food security; improve affordability and quality of housing; enhance educational opportunities; improve built environments and provide more green spaces and recreational opportunities; and increase financial security and economic opportunity may all positively affect health and reduce health disparities. Beyond these factors, any effort would be woefully incomplete if it does not also recognize and address racism and discrimination and long histories of stress and trauma affecting the health of individuals and communities and how they shape our systems and policies. Such efforts are challenging and complex and require strong leadership, community engagement, resources, and cross-sector collaboration to achieve progress forward.

— By Samantha Artiga | Jun 01, 2020